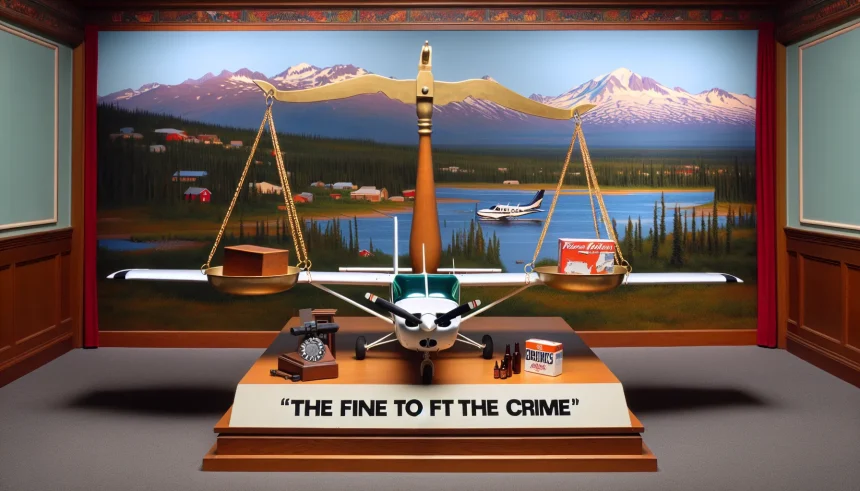

The U.S. Supreme Court is weighing whether to hear a case that could reshape how fines and forfeitures work in America. At the center is Ken Jouppi, a bush pilot from Fairbanks, Alaska, who lost a $95,000 Cessna after a passenger was found with a six-pack of beer in her bag in 2012. His conviction for bootlegging triggered the plane’s forfeiture. The question now is whether that punishment fits the Constitution’s protections against excessive penalties.

The case arrives at a moment when fines and forfeitures help fund parts of local justice systems. Supporters say the tools deter crime and remove instruments used to break the law. Critics argue they often exceed the offense and distort public safety priorities.

What happened in Fairbanks

Jouppi operated an air taxi service in Alaska’s Interior. During a 2012 flight, police discovered a passenger carrying a six-pack of Budweiser. That discovery led to a bootlegging conviction for Jouppi. The consequence was severe: the state ordered him to forfeit his $95,000 aircraft.

“The fine has to fit the crime.”

That simple rule, from the Constitution’s Excessive Fines Clause, now frames the dispute. Jouppi argues the loss of a plane far exceeds the gravity of the offense tied to a six-pack of beer. Prosecutors counter that forfeiture targets the tool used to commit a crime, a long-standing practice in many states.

The constitutional question

The Eighth Amendment bans “cruel and unusual punishments” and also “excessive fines.” Courts have struggled to define how far governments can go in taking property tied to a crime. The Supreme Court has said the Clause applies to states, but limits remain blurry.

In Jouppi’s situation, the issue is not whether the state can punish bootlegging. It is whether taking a $95,000 plane for conduct tied to a six-pack is out of proportion.

“The Supreme Court has been pretty mysterious about what that means.”

Legal analysts say the Court could clarify how to measure “excessive.” They point to factors like the value of the property, the seriousness of the offense, and the person’s blameworthiness.

Money and incentives in modern enforcement

The broader debate is about how fines and forfeitures support parts of the criminal justice system. Cities and agencies collect revenue from penalties and seized assets. Critics say this can create the wrong incentives.

“Hanging in the balance is an increasingly popular — and controversial — business model for criminal justice.”

Civil liberties advocates warn that high-dollar seizures can pressure defendants to settle or plead. They argue that ordinary people may lose cars, cash, or tools of their trade for relatively minor misconduct. Law enforcement officials respond that forfeiture removes the means to commit crimes and can fund victim services or safety programs.

- Supporters: forfeiture deters wrongdoing and disrupts illegal activity.

- Opponents: penalties often exceed the offense and strain public trust.

What the Court could decide next

The justices are considering whether to take Jouppi’s appeal. If they do, the case could set a clearer standard for when a fine or forfeiture goes too far.

Possible outcomes include a test that weighs the property’s value against the offense and the person’s role. A ruling could also guide lower courts on how to handle tools used in crime, like vehicles and aircraft.

For Jouppi, the stakes are personal. For cities, police, and defendants nationwide, the ruling could change how cases are charged, negotiated, and punished.

Whatever the outcome, the case highlights a simple idea with complex consequences. Penalties must be tough enough to deter crime, yet fair enough to respect constitutional limits.

The next step is whether the Supreme Court grants review. If it does, the decision could set new guardrails on fines and forfeitures and shape how justice is funded across the country.